My uncle raised me after my parents died. After his funeral, I received a letter in his handwriting that began with a sentence I still can’t read without shaking:

“I’ve been lying to you your whole life.”

I was twenty-six years old.

And I hadn’t walked since I was four.

Most people hear that and assume my life began in a hospital bed. But I had a before.

I don’t remember the crash.

I remember my mom, Lena, singing too loudly while cooking. I remember my dad, Mark, smelling like motor oil and peppermint gum. I remember light-up sneakers, a purple sippy cup, and having far too many opinions for a toddler.

I don’t remember the crash.

All my life, the story was simple: there was an accident. My parents died. I lived. My spine didn’t.

The state talked about “appropriate placements.”

Then my mother’s brother walked in.

Ray looked like he’d been built out of concrete and bad weather. Big hands. Permanent scowl.

“We’ll find a loving home,” the social worker said gently.

“No,” Ray replied.

She blinked. “Sir—”

“I’m taking her,” he said. “I’m not handing her to strangers. She’s mine.”

That was it.

He brought me home to a small house that smelled like coffee and motor oil. He didn’t have kids. Or a partner. Or any idea what he was doing.

So he learned.

He watched nurses closely, then copied everything. He kept notes in a battered notebook—how to roll me without hurting me, how to check my skin, how to lift me like I was heavy and fragile at the same time.

The first night home, his alarm went off every two hours.

He shuffled into my room, hair sticking up.

“Pancake time,” he muttered, gently rolling me.

He fought insurance on speakerphone, pacing the kitchen.

“She can’t ‘make do’ without a shower chair,” he snapped. “You want to tell her that yourself?”

They didn’t.

He built a plywood ramp so my wheelchair could clear the front door. It wasn’t pretty. It worked.

He took me to the park.

Kids stared. Parents looked away.

A girl my age asked, “Why can’t you walk?”

I froze.

Ray crouched beside me. “Her legs don’t listen to her brain,” he said calmly. “But she can beat you at cards.”

That was Zoe. My first real friend.

Ray did that a lot—put himself between me and the world and absorbed the awkwardness so I didn’t have to.

When I was ten, I found a chair in the garage with yarn taped to the back, half-braided.

That night, Ray sat behind me on my bed, hands shaking, trying to braid my hair.

It looked terrible. I thought my heart might burst.

When puberty hit, he came into my room with a plastic bag and a face so red it matched the logo on the pharmacy receipt.

“I bought… stuff,” he said, staring at the ceiling.

Pads. Deodorant. Cheap mascara.

“You watched YouTube,” I said.

“Those girls talk very fast,” he muttered.

We didn’t have much money, but I never felt like a burden. He washed my hair in the kitchen sink, one hand steady beneath my neck.

“You’re not less,” he told me whenever I cried. “You hear me? You’re not less.”

By my teens, it was clear there’d be no miracle.

So Ray made my room a world.

Shelves I could reach. A welded tablet stand. For my twenty-first birthday, he built a planter box by the window and filled it with herbs.

“So you can grow that basil you yell at on cooking shows,” he said.

I cried.

Then Ray started getting tired.

He moved slower. Sat halfway up the stairs to catch his breath. Forgot his keys. Burned dinner twice in one week.

He was fifty-three.

After the tests, he sat at the kitchen table.

“Stage four,” he said. “It’s everywhere.”

Hospice came.

The night before he died, he sent everyone away and came into my room.

“You’re gonna live,” he told me.

“I’m scared,” I whispered.

“I know,” he said. “Me too.”

“For things I should’ve told you,” he added quietly.

He kissed my forehead.

He died the next morning.

After the funeral, Mrs. Patel knocked on my door and handed me an envelope.

“Ray asked me to give you this,” she said. “And… I’m sorry.”

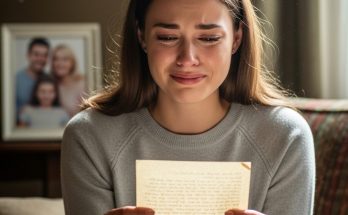

The letter shook in my hands.

Hannah, I’ve been lying to you your whole life.

He wrote about the night of the crash.

My parents were leaving town. They weren’t taking me.

Ray screamed at them. He saw my dad had been drinking. He could’ve taken the keys.

He didn’t.

Twenty minutes later, the police called.

He told me why he never confessed.

“At first, when I looked at you in that hospital bed,” he wrote, “I saw punishment. I resented you—not because of you, but because you were proof of what my anger cost.”

Everything after that, he said, was penance.

Then he wrote about the money.

The life insurance. The overtime. The trust he’d built quietly for years. The house he sold so I could afford real rehab.

“If you can forgive me,” he wrote, “do it for you.”

I sat there until the light changed.

He’d been part of what ruined my life.

And he was the reason it didn’t collapse entirely.

A month later, I rolled into a rehab center.

They strapped me into a harness over a treadmill.

“You okay?” the therapist asked.

“I’m doing something my uncle wanted me to do,” I said. “I’m not wasting it.”

Last week, for the first time since I was four, I stood with most of my weight on my own legs.

I shook. I cried.

But I was upright.

Do I forgive him?

Some days, no.

Other days, I think I’ve been forgiving him in pieces for years.

He couldn’t undo the crash. But he walked straight into what he’d done—every night alarm, every ramp, every quiet promise.

He carried me as far as he could.

The rest is mine.